This story is the third in a series on cultural battles facing the open-source community. You can read the first article, on ethics and licensure, here, the second article, on governance, here, and the fourth article, on open-source incentives and the trajectory of #EthicalSource, here.

* * *

The free software movement got started, at least in part, because of a really annoying printer in the MIT Artificial Intelligence Lab in the early ’80s.

The printer jammed all the time, so the lab’s employees figured they could save some time by adding a “jammed” alert to the printer’s software. But the code running on the machine itself was in binary — and, to the team’s chagrin, the source code was nowhere to be found.

Free software, which eventually spun out into the more corporate-friendly “open source,” was built on the idea that people who know how to program should be able to modify the software they use.

Then the internet happened.

As the web exploded, went mobile and expanded into virtually every aspect of our lives, it brought open source along with it. Today, open source powers everything, from the critical programs our doctors use to the apps on our phones. But you and I can’t modify that software. And that, Tobie Langel told me, is the seed of what he called a “crisis” in open source.

“We’ve moved from a place where software impacted people who were able to directly change it, to a place where software impacts people who don’t even realize software is impacting them,” said Langel, an open-source and web standards consultant. “And as a result, the ethos of open source, which was essentially based around giving agency to the person using the program, is no longer big enough.”

Who Is Responsible for Open-Source Ethics?

The average person with an iPhone may not be able to rattle off a proper definition of “software,” but the programs running on their devices affect them nonetheless — sometimes in good ways, sometimes in bad ways. Algorithms are biased. Apps are addictive. Data gets stolen or misused.

Discussions about the rights and well-being of end users deserve their own, thorough treatment, Langel said, largely because the issues are so complex. “User privacy,” for example, sounds like a desirable thing. But after working as a web standards consultant for companies like Google, Facebook and Microsoft, he knows privacy is difficult to navigate.

“Let’s say you completely remove ads from the web and use monetization, like subscriptions for everything. You’re essentially cutting off people with low revenue from access to information, right?” he said. “It’s not black and white.”

But some things, Langel said, are clear-cut. Like governments using software to coordinate actions that result in human rights violations — an oft-cited example is U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement’s use of Chef, a tool containing open-source code.

“We’ve moved from a place where software impacted people who were able to directly change it, to a place where software impacts people who don’t even realize software is impacting them.”

The people directly affected by ICE policies can’t go into that codebase and modify (or delete) it. But the developers who wrote the code can — and Chef developer Seth Vargo did. In that sense, the open-source ethos still stands: People who understand software can modify it.

But Vargo pulled his code in response to its use by ICE. Attempting to prevent its use would go against the official definitions of free and open-source software from FSF and the Open Source Initiative (OSI).

So, ordinary people seem too far removed from open source to be responsible for its ethics. Developers can’t draw boundaries around open-source ethics without running afoul of FSF and OSI. And companies and other organizations, presumably, won’t simply stop doing unethical things.

The answer, according to Langel and other members of the ethical source movement, is a redefinition of open source and a revamp of its internal processes. For ethical source founder Coraline Ehmke, that means protection for underrepresented developers and new licensure that accounts for ethics. For journalist and professor Nathan Schneider, that means new models of open-source project governance. For Langel, that means, among other things, some standards.

Standards and Priorities

Langel gave a talk at this year’s FOSDEM (Free and Open Source Developers’ European Meeting) conference titled, “Bringing Back Ethics to Open Source.” He toned the talk down considerably to avoid ruffling too many feathers, he said.

The next day, he heard Ehmke speak at CopyleftCon, another free and open-source software conference. She gave the talk he’d wanted to give.

“You write something, and it’s really hard because you want to pour everything that you really care about into it, but you’re also concerned about the impact it could have on your professional life,” he said. “And you do all of that, and then you read someone else’s [work], and you’re like, ‘Dammit.’”

That was the beginning of Langel’s involvement with ethical source, but the direction of the free and open-source software movements had been on his mind for a while.

It started with web standards, or the technical specifications for building websites and the technologies that support them. Langel served as testing lead at the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), represented Facebook’s advisory committee at the W3C and edited web standards including Web IDL, which laid out the language used to define web interfaces.

Web standards and open-source software serve a similar purpose, Langel said: Creating a level playing field for people to build on existing technologies. But their trajectories have been incredibly different.

“A lot of the practitioners of open source come from this old culture where the only thing that really matters is that you as a developer — as a computer-savvy person — are able to modify the program that you run.”

Take the “priority of constituencies” native to web standards development. The W3C document “HTML Design Principles” defines the priority of constituencies this way: “In case of conflict, consider users over authors over implementers over specifiers over theoretical purity.”

In other words, when web developers disagree over something, they should go with whatever option makes life better or easier for everyday people sitting at computers and browsing the web. Those end users should be considered before people building websites, who should be considered before people building browsers, who should be considered before people writing standards, who should be considered before technical purity — or the simplicity and consistency of the code itself. That’s because there are way more end users than standards writers, and one hour of work by those standards writers could save billions of collective hours of work for web-surfers at home.

This hierarchy laid the groundwork for the W3C’s review processes around privacy, security, accessibility and more.

“But all of these aspects are completely lacking from open source,” Langel said. “And no one is willing to have this conversation at the present, because a lot of the practitioners of open source come from this old culture where the only thing that really matters is that you as a developer — as a computer-savvy person — are able to modify the program that you run.”

Langel’s web background gives him a different perspective, he said, and he thinks it’s time the open-source community takes a page from W3C’s book.

A New Open-Source Hierarchy

W3C’s priority of constituencies is reminiscent of the open-source Apache Software Foundation mantra, “community over code,” Langel pointed out during a recent talk at State of the Source. The difference is, web development defined its constituencies and created a hierarchy of needs; open source never has.

That might be because open source’s constituencies have changed so dramatically: Back when a defective printer sparked the call for free software, software’s developers and end users were largely the same people. Today, there’s an entire ecosystem of individual and corporate maintainers, individual and corporate contributors, end users, innocent bystanders (or people affected by software who aren’t using it themselves), cloud infrastructure providers and app developers.

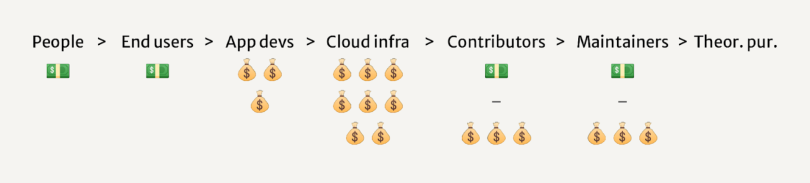

If open source were to arrange its constituencies the same way W3C did, it might look something like this, Langel said: People over end users over app developers over cloud infrastructure over contributors over maintainers over theoretical purity. (If this order seems weird, consider this: A technical change that takes a project maintainer one hour could easily create hundreds of hours of work for a cloud infrastructure provider.)

Simply arranging those players into a line illustrates some of the questions dogging open-source communities. Like, why do the people with the most responsibility — maintainers — make the least money? Why are the contributions of corporate contributors with plenty of financial backing treated the same as the contributions of independent contributors who don’t receive any compensation for their time? Why don’t we hear more talk about how open-source software affects “people” — you know, that constituency at the top of the hierarchy?

A Community Divided — or Not

Free and open-source software was meant to give end users more input into the software they consume; it hasn’t. Big business was supposed to lose ground; it didn’t.

“The guarantees open source offers are no longer present,” Langel told me.

But does that disconnect matter to the open-source community at large?

Just nine months ago, Langel was nervous to share his real feeling about open-source ethics at a conference talk. During our interview, he lamented that “no one” is willing to have a conversation about open-source standards and review processes.

But he also mentioned a Twitter poll he posted on February 6 — just three days after hearing Ehmke speak at CopyleftCon — asking whether people supported adding language to the popular MIT License forbidding the use of open-source software in violation of human rights. Fifty percent of the 1,200 respondents said it was a “great idea.”

This, according to Langel, is one of many indications that free and open-source software’s governing bodies are out of touch with the community’s sentiment. For instance, OSI clapped back when Ehmke’s first draft of the Hippocratic License — a software license that prohibits human rights violations — implied that the projects that use the license would still be open source.

“The intro to the Hippocratic Licence might lead some to believe the license is an Open Source Software licence, and software distributed under the Hippocratic Licence is Open Source Software,” the initiative tweeted. “As neither is true, we ask you to please modify the language to remove confusion.”

A few months later, OSI co-founder Bruce Perens used a pseudonym to submit “The Vaccine License,” a license that requires users vaccinate themselves and their children, for OSI review. It was rejected. In a PowerPoint posted to YouTube in August, Perens acknowledged the license was meant as “a joke/test/sarcasm,” arguing that ethics should not be upheld in copyright court.

“The guarantees open source offers are no longer present.”

That’s why, when Langel ran for a seat on the OSI board last spring, his gripe was with OSI itself.

“How I organized my campaign was to say that OSI being the custodian of the term ‘open source’ is a problem,” Langel said. “As custodian, it has to reflect not what a few of its members care about, but what the overall community believes.”

That overall community is changing, and many young contributors don’t remember the purists’ 30-year fight for the current definitions of free and open-source software. If you asked a twenty-something developer today what open source is, you’d probably hear something that sounds very little like an actual open source license — “I can share it, and other people can use it.”

If you asked if they’d like government agencies to use the software they built to round up and detain immigrants, Langel said, you might get something akin to, “Fuck no.”