With the University of Southern California’s campus on lockdown, Alvin Huang, the founder and design principal of Synthesis Design + Architecture and an associate professor at the USC School of Architecture, was self-quarantined at home, working under the light of a 3D-printed lamp.

The coronavirus was expected to reach its apex in Los Angeles within the week and the situation at Keck Medicine of USC, where his wife Elizabeth Mojarro Huang is the clinical research coordinator, was grave: internal hospital data predicted the need for 6,095 masks and 6,000 face shields — above the number of true, medical-grade N95 masks and face shields that could be reliably sourced in time.

But the designer of swooping high-rises and space-age mixed-use buildings wasn’t ready to accept the situation as irremediable.

Rapid response coordination Via Slack

Huang’s studio uses 3D printers to create building models, prototypes and bespoke furnishings. Recognizing the need for a Plan B to fill the projected gap in personal protective equipment at Keck Medicine and other Los Angeles hospitals, he sent out an “open call to arms,” under the banner USC Architecture #Operation PPE. He urged a volunteer network of USC Architecture faculty, students and alumni to 3D print hospital-approved masks and face shields at their homes or offices.

While not true N95 masks, they had been authorized for emergency use by a team led by associate professor of research radiology Daryll Hwa Hwang, who had determined they could reduce the risk of infection for medical professionals on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The next thing I knew,” Huang said, “I had the mayor’s office of Los Angeles calling me and saying, ‘How can we ramp this thing up?’”

He sent out an email to other firms in his network and the effort quickly swelled. “Instagram and Facebook posts started to go viral. A CBSNews local affiliate called for an interview on Zoom and it was on the evening news in LA. It just skyrocketed,” Huang said.

The alliance is coordinated by an active Slack group that coordinates drop-offs and pickups of product and materials.

According to a briefing he shared with Built In via email, the group consists of 207 volunteers with 200 3D printers distributed throughout Southern California and beyond. In less than a week, they have printed 1,156 mask components that come close to fully equipped N95 masks in performance, as well as 575 face shield visors. They plan to distribute the equipment to Keck Medicine, Los Angeles County+USC Medical Center, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, and Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital in Watts.

The alliance is coordinated by an active Slack group, “where we share questions, tips and results; coordinate drop-offs and pickups of product and materials; and exchange about various issues as they arise,” the report states.

3D-printed masks are The ‘Back Up to the Back Up’

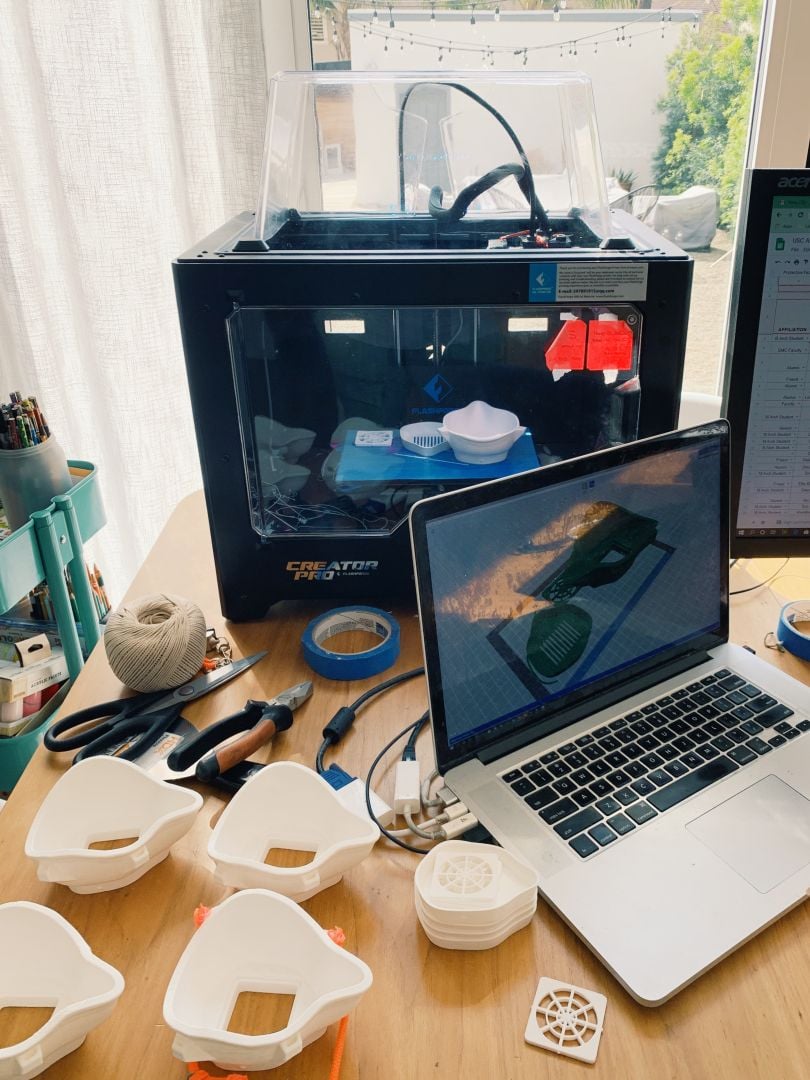

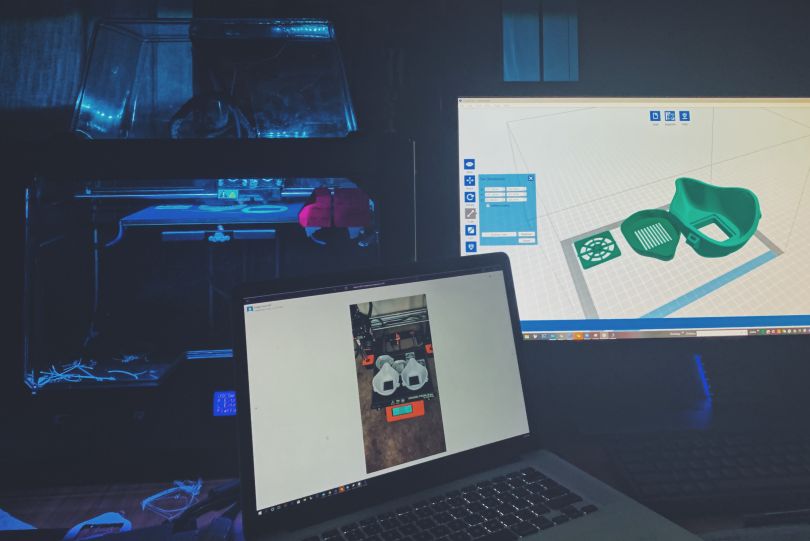

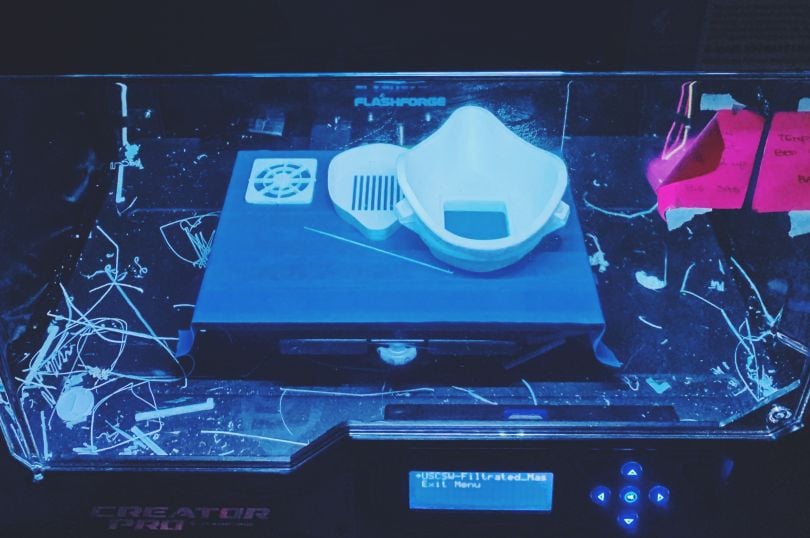

As a studio, Synthesis Design + Architecture is a relatively small operation. The firm has just two 3D printers, a MakerBot Replicator 2 and a Flashforge Creator Pro, which Huang describes as “glorified, highly precise hot glue guns.” (The Creator Pro seen above is now at his home). The printers read stereolithography (STL) files native to CAD software, the 3D design equivalents of un-editable PDFs. Feed a spool of polylactic acid (PLA) filament into the printer carriage and a roving gantry arm passes back and forth with a low hum, laying out ribbons of hot plastic like lines of toothpaste.

Even relatively inexpensive models are highly accurate, Huang said, with an error threshold within 0.1 millimeter. Leaving no gaps or seams, they can produce a very close approximation of key parts used in N95 masks, including a muzzle-like plastic shell, a ventilated nose cap and a gridded hatch to secure an air purifier filter. But with just two printers, each with a rough print time of 3.5 hours per mask, Huang’s office, or any other firm alone, could hardly make a dent in the projected supply gap. He envisioned a larger coalition of “minutemen,” who, working remotely in a coordinated network, could 3D print component parts at scale.

Importantly, 3D printers are not designed to produce filters. Earlier this year, several experts explained to Built In that N95 masks require a filter made with “a special kind of synthetic fabric, melt-blown fabric, made from ultra-fine fibers about one-tenth as thick as a strand of hair. Few, if any, 3D printers can print at that level of precision, let alone at any reasonable speed.”

But, by the terms of the joint Keck Medicine and USC School of Architecture emergency protocol, hospital staff will sterilize and assemble the 3D-printed parts on site and add a Honeywell HEPA (high efficiency particulate arresting) Clean Air Purifier U Filter, an available consumer product “certified to remove 99.97 percent of microscopic particles as small as 0.3 microns from the air.”

Citing a National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine report, Forbes notes that the designation N95 means a filter “can filter out at least 95 percent of particles of all sizes from the air,” including “something less than 0.1 microns in size,” — a much more stringent deterrence threshold.

And Huang is quick to point out that the gear is the “back up to the back up” — a step above clinicians “wearing handmade masks, bandanas and socks.”

vetting open-source STL files

Still, during a time of crisis, the components could fill a critical hole in the medical equipment supply chain. Many, perhaps thousands, of open-source 3D mask designs can be found online, Huang said, but most are untested. With printable STL files and instructions approved by Keck Medicine, students, architects and engineers have a more trustworthy standard.

As of last week, 10 universities, more than 30 architecture or engineering firms and several nonprofits, including the 3D Collaborative Network, Downey Foundation for Educational Opportunities and Foundation for the Building Arts, had joined the initiative. A full list of participants and inventory systems is available on a Google Sheets spreadsheet.

“Most architecture firms have 3D printers and materials for models of buildings; they’re standard tools. When we saw that an open-source file was made available publicly it seemed like a no-brainer.”

Patrick Tighe, principal of the eponymous architecture firm and a professor at USC, was one of the earliest collaborators, working with Huang to promote the project. With printers working around the clock, employees of his office had printed 25 masks last week, with plans to reach 50-100 by Monday of this week.

“Most architecture firms have 3D printers and materials for models of buildings; they’re standard tools. When we saw that an open-source file was made available publicly it seemed like a no-brainer. If we pitched in and even made a small contribution, it would certainly make a difference,” Tighe said.

Architects at the Los Angeles and Ft. Lauderdale offices of the firm Brooks + Scarpa have also been busy printing masks and shields, said principal Larry Scarpa. With 80 percent of employees working from home, much of the printing is being done outside the office.

At first, the firm used STL files developed by Cornell University architecture professor and Associate Dean for Design Initiatives Jenny Saben, whose practice lies at the intersection of architecture and computational material design. By switching to the Keck Medicine approved STL files, which produce thinner, more materially efficient masks, they have cut printing time from 2.5 hours per mask to roughly 40 minutes per mask.

Brooks + Scarpa delivered more than 100 approved masks to Broward Health Medical Center; Florida Atlantic University Student Health Services; Lighthouse of Broward, an organization for the visually impaired; and the Fort Lauderdale Fire Department on April 4, and they continue to run six printers through the night — a guerrilla operation they started weeks before Operation PPE officially launched.

“We’re not trained to improve these things. We made an important decision to say we are here as muscle not as brains.”

The production efforts of the Los Angeles firms represent just a small fraction of what is being done nationally. Huang said Operation PPE has received $10,000 in funding from the AIA California Council and additional funds from undisclosed individual donors. He is in talks with Warner Brothers, Gruen Associates, the LA mayor’s office and the Brooklyn-based 3D-printing company MakerBot for additional funding and in-kind support. He’s also working with the USC School of Architecture to set up a formal mechanism for tax-deductible donations.

Components donations instructions specify that donors deliver raw 3D-printed parts in bags to 12-gallon drop-off bins at five locations in Los Angeles and South Pasadena between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. The bins are serviced by student volunteers and a designated “runner.” They are tagged and tracked with a dated delivery slip that describes the components, the 3D printer and materials used to create them, and the provider’s name and contact information.

Rapid Cluster Printing

Though spearheaded by architects, many of whom spend their lives and careers designing three-dimensional objects — not just buildings — the project is less a design accomplishment than a rear-guard logistics feat, enabled by the cloud.

“We’re making a conscientious effort to quell members’ desire to improve everything that comes into their hands in this particular instance,” Huang said. “We’re not trained to improve these things. We made an important decision to say we are here as muscle not as brains.”

The budding strategy, discussed over a Zoom call with 50 coalition members across southern California on April 1, is to organize print farms capable of “rapid cluster printing” and eventually transition to mass production in a more conventional sense. In a month, Huang said, he hopes Operation PPE will be producing 50,000-100,000 masks per week.

His more immediate wish is for Plan B to remain just that — a stop-gap measure. “Our doctors should not be fighting for resources,” Huang said. “Hopefully, they’ll never have to touch the stuff we produce.”